At North Mead Primary Academy, we offer a curriculum which is broad, balanced and builds on the knowledge, understanding and skills of all learners, whatever their starting points as they progress through each Key Stage. The curriculum incorporates the statutory requirements of the National Curriculum and other experiences and opportunities which best meet the learning and developmental needs of the learners in our academy.

Our Immersive Book Based approach enables children to make links between their learning and build effectively on prior knowledge. The aim of our curriculum is for children to have the requisite skills and acquire the knowledge from agreed concepts to be successful, independent and motivated learners in readiness for the next stage of their education.

If you do not find what you are looking for, please feel free to come to the school office where we will find someone to help you.

Curriculum Intent

“We will provide all of our children with a broad, relevant and enriched curriculum so that they have the character to make a positive contribution to our society and are knowledgeable, skilled and ready for the next phase of their education.”

Quality First Teaching

North Mead’s curriculum is coherently planned and sequenced so that it builds skills, knowledge and understanding in a progressive way. Reading is at the heart of the curriculum as well as our Curriculum Drivers; we aim to link the learning together so that our pupils understand where and how their knowledge fits in the world.

The whole school curriculum overview provides a summary of each topic and subject focus for each year group. This overview outlines the overarching themes, stimulus and core texts that will be used throughout the year to engage pupils in the learning. It includes a brief summary of the learning outcomes that the children in each year group will achieve by the end of the academic year. This planning ensures that there are rich and thoughtful stimuli for learning in place in order that a rich and engaging curriculum is provided for pupils.

Knowledge Organisers provides the knowledge that the children need to know and the key vocabulary.

Your Content Goes Here

What we teach (the subject content) is as important as how we teach (pedagogy). That might seem like an obvious statement, but it’s often underestimated.

The importance of subject knowledge is recognised in the teacher standards:

- TS2 (promote good progress and outcomes by pupils)

- TS4 (plan and teach well-structured lessons)

- TS5 (adapt teaching to respond to the strengths and needs of all pupils)

- TS6 (make accurate and productive use of assessment)

As a primary school North Mead teachers need to know the foundational knowledge and what progression looks like over time in 13 subjects.

Without good knowledge of what they are teaching, it is impossible to meet these standards in a meaningful way. For example, one has to know what good progress looks like in a subject area and what is being assessed to promote good outcomes and make productive use of assessment.

As teachers of subjects, teachers need to develop an understanding of vital subject content, how to sequence it over time, and what misconceptions pupils are likely to develop and how to overcome them. It makes sense that those who educate specifically in the teaching of a subject must also have well developed subject knowledge. This must be paired with pedagogical content knowledge – that is an understanding of what to teach in what order, how to communicate it, and what common misconceptions might arise. Only if this is the case can the teacher effectively model, guide and prompt what good practice in those standards above consists of.

10 top tips for improving your subject knowledge

- Make use of Youtube, podcasts, BBC and other media formats and platforms. We live in an age where we can find videos, clips, documentaries, podcasts, radio shows and more on whatever we wish to search. If you know you’re going to be teaching about the Romans, find a documentary about Roman civilisation and give it a watch! If you know you’ll soon be teaching A Christmas Carol, listen to a podcast about Victorian life.

- Follow educators on Twitter. Twitter is a wonderful resource for teachers and often, educators share resources and links to platforms that have helped them to develop their subject knowledge. There are also Twitter pages dedicated to individual topics and subjects, for example, @GCSE_Jekyllis a page that solely tweets thoughts and analysis on the text of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde – perfect subject knowledge enhancement for secondary school English teachers. Searching hashtags is also a good place to start.

- Read revision guides and textbooks.Revision guides and textbooks can be picked up cheaply (many charity shops have guides that have been donated by those who have finished their studies) and are excellent for providing explanations and practice questions you can use to check your own understanding.

- Keep a subject knowledge notebook. Have a notebook for each subject if you teach primary, or a notebook for each topic within your subject if you teach secondary, and record ideas and notes as you go. By doing this, you’ll create a guide for yourself that you can dip back into when you’re about to teach a topic again.

- Know the National Curriculum.Ensure you know what pupils are expected to learn within each subject. This is a good way of ensuring your own knowledge far exceeds where the pupils need to get to.

- Become familiar with mark schemes, assessment objectives and curriculum maps. Knowing what content pupils will be taught at any given time, how this links to what comes before and what comes after, and how pupils will be assessed will ensure you are always ahead with your own knowledge. Use curriculum maps to conduct a personal subject knowledge audit, identifying the topics you feel confident teaching and the ones where you need to brush up on your knowledge.

- Test yourself. Quiz yourself, sit timed exam papers like those you would expect your pupils to do, work through maths problems and so on. Not only will this be useful for identifying gaps in your knowledge (which will then influence what you focus your studying on) but it will help you to understand what your pupils go through and what they are expected to produce within a given timeframe.

- Read around each topic.Becoming an expert in the topics you teach reaches beyond just knowing the content the pupils need to know. Be curious about the topics you teach and read around them. The British Library contains a wealth of information and resources relevant to topics such as English, history, religious studies etc.

- Attend subject knowledge CPD. Many schools hold subject knowledge CPD sessions and it’s worthwhile going along. If this isn’t an option, see if there is a subject knowledge conference happening in your area, or one you can attend online.

- Complete a Subject Knowledge EnhancementThere are subject knowledge enhancement courses across the country that can be taken either prior to starting teacher training or alongside your teacher training course. Alternatively, other websites such as FutureLearn have a variety of online courses you can take in individual topics.

There is plenty you can do to improve your subject knowledge which will, in turn, improve your teaching practice. It’s much easier to teach a topic you feel secure in, so make sure you regularly reflect on your subject knowledge and identify the areas you need to develop.

Useful resources to support subject knowledge

- National Curriculum Key stages 1 and 2 framework

- Statutory framework for the early years foundation stage

- Bold Beginnings

Phonics and Reading

- Synthetic Phonics and try to notice what the teachers and children are doing and saying. How do your observations compare with your memories of learning to read and write?

Brooklands School

Marner School - the DfE’s 2022 guidance for schools on early reading: The reading framework: Teaching the foundations of literacy

Maths

- For some innovative maths ideas, resources and research about mathematical learning and teaching youcubed.

- There are some ‘knowledge checks’ (as well as loads of resources and videos on maths topics) on this Sage website. You can use this website to check what areas of maths you are more and less confident in, and then use the resources to help to develop your mathematics subject knowledge of the primary curriculum.

- The National Centre for Excellence in the Teaching of Mathematics (NCETM) has a large amount of information and resources for practicing teachers to support their mathematics teaching. You might want to have a look at their professional development materialsto develop an understanding of how mathematics is taught in many schools.

Science

Art and Design

Computing

Design and Technology

Geography

History

Languages

Music

Physical Education

RSE

Positive Relationships

Pupils are taught about social interactions and such pro-active conversations supports the development of oracy, social and emotional regulation and positive wellbeing.

A range of strategies embedded across the school are used to reinforce social and emotional learning and regulation including:

- Unconditional Positive Regard

- Consistent use of the behaviour policy by all teaching staff

- Debrief conversations

- Team Tactics

- ELSA support

- Additional support including MHST

- Kindness Crew

These are part of our wider Graduated Response strategy – please read that for more information.

Below is an interesting extract from Tom Bennett’s book – Creating a Culture:

Get in front of their behaviour

Good behaviour is fundamental to all education objectives, but too often teachers lack a structured approach to optimising behaviour – what should they do?

- Struggling – many teachers struggle with behaviour. The most common reason is because they wait until misbehaviour happens, then react to it. The solution? Get in front of the behaviour by shaping the behaviour culture.

- Classroom culture – culture simply means the shared beliefs and values of a group. Classes have cultures whether you want them to or not. Behaviour is influenced massively by the culture.

- Making the weather – you make the weather. Teachers need to be the conscious architects of the classroom culture. They need to define what good behaviour means first. This gets in front of the behaviour.

- Social animals – all humans are social animals. We take behaviour cues from our peer group, and those around us. Unconsciously, we try to fit in, to conform. We often try to behave normally (for that culture).

- Normative messages – we can use this consciously and persistently, immersing students with normative messages – what normal behaviour means. This can mean formal school rules, expectations etc. and is communicated by words, actions and the environment.

- Routines – another technique is by building routines. These are short, clearly defined sequences of behaviour that enable us to know automatically what I need to do and when – e.g. transitions, lesson entry, lesson ends…

- Communication – the best way to communicate all behaviour instructions is to make sure they are always: clear (unambiguous), concrete (give examples) and sequential (do x, then y, then z)

- Behaviour feedback – lastly, teachers must use effective behaviour feedback mechanisms i.e., sanctions and rewards, but also reinstruction, nurture, consequences etc. Sanctions must be highly consistent, or they lose efficacy. Rewards can be less so.

Skills for learning are broken up into six areas at North Mead: Readiness, Resilience, Resourcefulness, Reflectiveness, Responsibility and Risk Taking. They are taught and nurtured across all areas and ages by referring to the ‘6Rs’ and are represented by six animals for the pupils to relate to.

In order to secure progression in learning behaviours, it is important to ensure they are incorporated into all lessons and all areas of school life. In order to achieve the highest possible outcomes pupils must understand that learning is a process not just an outcome on a test so that they become lifelong learners.

| What are we looking for? Overview of North Mead’s Team Tactics. | |

| Be Ready | “We are always punctual, organised and prepared.” |

| Character Muscles · Concentration: The act of focusing your attention. The art of not being distracted. · Independence: Not relying on others to do things for you. Showing that you can learn to do things for yourself. · Curiosity: A strong desire to know or learn something. Asking questions to learn more. · Self-Efficacy: Believing that through your actions you can achieve. | |

| Be Respectful | “We listen to and value others.” |

| Character Muscles · Friendship: Involves trust, generosity, sharing, empathy and more. Shouldn’t be treated lightly or traded away. · Humility and Gratitude: Being modest and not showing off. Being thankful and showing appreciation. · Kindness: Being generous, thoughtful, and friendly. · Self-Esteem: Feeling good about yourself and others. | |

| Be Responsible | “We look after each other and the environment.” |

| Character Muscles · Managing Impulsivity: Restraining yourself from doing something that may not be appropriate at the time. Involves self-control. · Integrity: Being honest and telling the truth. Doing the ‘right thing.’ · Good Humour: Being in a good mood and trying to brighten other people’s mood. · Empathy & Compassion: The ability to understand other people’s feelings and find the best way to help or comfort them when they need it. | |

| Be Reflective | “We think about our learning and our behaviour.” |

| Character Muscles · Questioning: Asking questions if you’re unsure. Asking questions to develop deeper understanding and asking why. · Making Links: Thinking in depth and connecting ideas and skills together · Problem Solving: Using a variety of strategies and resources to help you solve something difficult. May involve perseverance. · Meta-cognition: Thinking about your own thinking and learning and being aware of what you are doing. | |

| Be Resilient | “We never give up, even when it gets difficult.” |

| Character Muscles · Perseverance: Not giving up even when something is difficult, or you’d rather be doing something else. · Revising/Improving: To make something better, in any way, than it already is. · Confidence: Believing in yourself and your abilities. Not being shy of trying. · Courage: The ability to face challenges, even if they are daunting. Appropriate risk-taking is trying things even if they may fail. | |

| Show Reciprocity | “We exchange things to benefit all.” |

| Character Muscles · Imitation: Using something or someone as a model to learn from. · Listening/Communicating: Listening politely and respecting other people’s ideas. Sharing your own ideas freely and clearly with others. · Co-operation: The ability to work together. May involve compromise or self-sacrifice. · Teamwork/Inclusiveness: Allowing others to join in and not limiting yourself to certain people. | |

Reviewing previous learning

By dedicating a short period each lesson to reviewing and evaluating previous academic performance, children will perform better academically. As our cognitive load is quite small, if we don’t review previous learning, then the effort of trying to remember old information will get in the way of learning new information.

By devoting time to review and evaluate previous learning, children will ultimately perform better. This is because they will develop a more in-depth understanding of syllabus material, make connections between topics, and enhance their critical thinking skills.

Possible activities to review learning:

- Correcting homework

- Reviewing concept or skills utilised in the previous homework

- Asking students where they struggled

- Reviewing the material where errors were made

- Reviewing material that needs overlearning (i.e. newly acquired skills or information)

- Ask questions

- Use pair work

- Low-stress quizzes and games

Doing these sorts of tasks ensures that there is a firm foundation for future learning to occur.

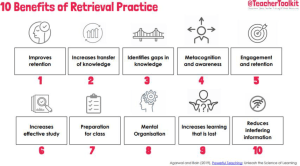

Retrieval

Each lesson starts with a recap/consolidation of previous learning. This is used every lesson to ensure that the start of lessons are settled, focused and contextualise the learning for pupils.

It allows for retrieval and recall of prior learning, they also allow the adults to assess starting points so that pupils can be grouped and supported appropriately.

The best teachers are those that recognise and overcome the limitations of their children’s cognitive load by teaching material in small steps. These teachers adopt this sequential learning approach to ensure that their children have mastered a concept before moving onto the next step. Children mastery is assessed both through retrieval practice and knowledge application.

Breaking down learning into small steps requires time, but the pay-off is worth it as doing so:

- Makes the task more manageable

- It allows children to make steady progress

- It allows children to make connections in their learning

- It allows children to understand why each step is important

- It allows teachers to assess children’s progress more quickly

Cognitive Load Theory

Cognitive Load Theory emphasises how our working memory, which is where we initially store new information, has a limited capacity. For learning to occur, this information needs to be transferred to the near-unlimited capacity of our long-term memory. Unfortunately, there is a bottleneck between the two, meaning that information that doesn’t get transferred across is ultimately lost and forgotten.

As our working memory is so small, if children are presented with too much information at once, their brain can suffer from something known as cognitive overload. When this occurs, the learning process slows down and can even stop, as the brain can no longer process all the information being presented at that one time.

By presenting information in small steps, teachers will be better able to organise the learning material in a way that allows for information to be transferred to the long-term store, improving memory recall.

In the classroom:

- Use worked examples – Worked examples are a great tool for teachers to reduce the load placed on their children’s working memory by showing the steps needed to achieve a particular task. When children are given problems to solve, all their focus is on how to solve the problem rather than what steps they took. Consequently, when children look over past answers to problems, they often can’t remember how they got there.

- Use completion tasks – Completion tasks are another effective way for teachers to break down a complex task. Unlike standard worked examples where children don’t really interact with the material, completion tasks are worked examples that are completed partially. Therefore, children are forced to apply their knowledge by completing the rest of the task themselves. This enhances learning as it pushes children to expand and apply their knowledge but should not overwhelm them.

- Reduce the amount of information on your slides – Although it may be tempting to include a lot of information on your slides and add fancy animations to make your presentation more fun and interesting, you would actually be hindering your children’s learning. Too many words on the slides? Children will likely remember a lot of redundant information. Too many fancy animations? Children will likely remember the animations more than the actual content.

- Use instructions – In his book on the Principles of Instruction, Tom Sherrington suggests that teachers can simplify a complex task by providing children with clear step-by-step instructions on what to do. Rosenshine uses the example of learning how to summarise the information in a paragraph:

- Teacher identifies the main theme of one example paragraph;

- Teacher identifies the main themes of different paragraphs;

- Teacher presents a new paragraph and asks the class questions about the paragraph;

- Teacher supervises as students learn to summarise the main theme on their own;

- Teacher then models how to identify the information that supports these themes;

- Teacher supervises students attempt at identifying these supporting themes.

Since learning is not a process that teachers can directly observe, there has to be another way to check for children’s understanding. The best teachers aske the most questions and ask children questions about how they got to their answer.

This is because questions are a great way for children to practice rehearsing new material and make connections with previous learning as children are forced to discuss their thoughts. Not only do questions show whether students have understood what you’re trying to teach them, but they also reveal which children engaged with the previous lesson.

If a children can’t answer a content-related question, this indicates that further instructional teaching is necessary before moving onto the next stage of the lesson.

In the classroom:

Questions are important, but you have to be asking the right questions as well. As a teacher, there are several effective questioning strategies you can use to consolidate your children’s learning:

- Ask pre-questions – pre-questions are things you can ask your children about material that they have not yet learned. Research shows that students who had been asked pre-questions were later able to recall almost 50% more information than their peers who had not. They were also able to remember other key information from the lesson too.

- Elaborative interrogation – while pre-questions are used before we teach the material, elaborative interrogation is a strategy that is used afterwards. This involves asking students ‘why’ questions, such as:

- ‘Why would this be true?’

- ‘Why would this not be the case?’

- ‘Why do you think that?’

Doing so forces them to think harder and deeper about the material, with several studies finding that this enhances how much they remember in their long-term memory.

These sort of probing questions are a great way to challenge your children’s understanding and allow you to guide their learning. essentially, you are engaging in a funnelling technique by initially asking a child a broad question and slowly getting more specific. This process allows your children to explore their understanding of a topic in more depth and from a different perspective that they may not have thought of.

- Use self-questioning – Self-questioning is an effective metacognitive strategy as it encourages children to think more deeply about the material they are studying. This leads to stronger connections, making it easier to retrieve the information at a later date as children are forced to focus their attention and interact with the presented information.

Questions such as ‘why does it make sense that…?’ and ‘why is this true?’ are great examples of the what children should be asking themselves. Asking these questions will improve how much your children learn, how quickly they learn and, subsequently, how well they perform academically.

- Use cold calling – Cold calling is when you ask a child to answer a question when their hand isn’t raised. Research shows that classes with “high” cold-calling rates caused children to volunteer to answer more questions over time. The number of children raising their hand to answer a question also increased.

By participating in classroom discussions more and more, students felt it was easier to offer their opinion and answer questions.

In the classroom:

Rosenshine himself suggested 6 question templates that can be helpful to get your children to engage with their learning more deeply and to gauge their level of understanding, so you know which areas need more work. These questions are:

- “What is the main idea of …?”

- “What are the strengths and weaknesses of …?”

- “How does this tie in with what we have learnt before?”

- “Which one is the best … and why?”

- “Do you agree or disagree with this statement: …?”

- “What do you still not understand about …?”

Teachers need to model their thought process when presenting new material to children. By breaking down a task and showing children how to complete it, teachers can help children learn more effectively. If you want children to actively engage with their learning and develop a fundamental understanding of how to develop a skill, you need to show them how to do it. Not only does it make the topic easier to understand, using visual examples reduces their confusion as well.

Modelling thought processes in the classroom is a branch of Vygotskian ‘scaffolding’. When modelling how to complete a problem-solving task, the teacher describes which steps they are taking to solve the problem and why they’re taking those steps. By breaking the task down and explaining each step, you’re guiding children’s learning.

However, modelling your thought process and explaining why you came to your specific decision can be quite challenging. But by providing a ‘mental model’ and sharing your own understanding and experiences, you help your children develop the same skill.

Research shows that the interactive process of providing ‘mental models’ to encourage and guide children practice enables children to become critical thinkers. This is because children are allowed to actively interact and reflect on the material they need to learn, consequently performing better academically by making complex concepts more accessible.

In the classroom:

- For it to be effective, modelling behaviour and thought processes need to be carefully organised to ensure your children are getting the appropriate guidance for their academic level. Model too much and your children won’t get enough time to practice retrieval themselves. Fade out your support too quickly and your children won’t grasp the concept correctly.

- Model your thinking – If your thoughts are not organised, are long-winded and not solely focused on the task you’re trying to explain, you’re going to confuse your children and they won’t remember anything. Research suggests that the best models are clear and concise so children can easily follow your direction of thought and replicate the task independently. Avoid using abstract reasoning to explain a concept.

Make sure that your demonstrations of how to complete a task are brief, broken down into small steps and are consistent with what you are trying to showcase. If a task is particularly complex or new, several examples of how to approach the task should be narrated, explained and clearly organised.

- Use worked examples – Worked examples are a useful way to show your children the steps they need to take to complete a task correctly and to keep them focused on what they are meant to be doing. If you explain and showcase examples of each stage of the process, children develop a clearer understanding of what is being asked of them. This act of providing a template frees up working memory space, which allows them to primarily focus on the task at hand.

- Use completion tasks – Completion tasks are one step above worked examples as they require children to actively interact with the material and do more of the problem solving themselves. Essentially, you’ve modelled the thought process of what they need to do and now they need to apply that knowledge to complete the task on their own. By slowly providing less support, children are challenged to practice their newly acquired skills, enhancing long-term recall.

- Break it into chunks – Rosenshine suggests that the best teachers take a sequential learning approach to provide their children with an opportunity to fully master a concept before moving onto the next part of a topic. By deconstructing the process of solving a complex task into more manageable chunks, you give children a clear understanding of what is expected of them when practising on their own.

- Ask probing questions – Rosenshine has emphasised the importance of asking questions because of their impact on cementing children’s learning. When modelling a thought process or demonstrating how to complete a task, you must ask questions regularly to ensure that you’re modelling processes effectively and not causing confusion.

One type of question you can ask your children are ‘probing questions’ as these are a great way to see if children are following your thought process and are being guided effectively. Asking questions such as “how would you expand a quadratic equation?” and “why do we need to expand quadratic equations to solve the question?”, you’ll encourage children to think critically.

The art of explanation and modelling is vital to the quality approaches of teaching which we provide the children at North Mead.

The most successful teachers are those that spend as much time as possible guiding student practice. It’s not enough for children to learn something once before completing tasks independently; they have to keep rehearsing this information if they want it to be stored in their long-term memory. And teachers are in charge of guiding this process.

We believe that teachers need to be spending more time cultivating a classroom environment that provides children with the opportunity to practise retrieval with the material they’re learning. The more children can practise rehearsal, the easier it becomes to retrieve this information from their long-term memory when they need it.

Children need enough time to practise retrieval, ask questions, and get the help they need to further develop their understanding. This allows them to make connections between their new learning and old knowledge as they’re forced to think more deeply about how this new material fits into the bigger picture.

It’s important that teachers don’t rush this process, as the less time children spent practising the material, the less they’re going to be able to do with it. Practising with the new material may include:

- Summarising

- Elaborating

- Rephrasing

- Evaluating

- Apply this new knowledge

It is important that teachers guide this practice, in order to reduce the likelihood of children practising errors and rehearsing incorrect information.

In the classroom:

- Ask questions: Questions are a great way to check for understanding.

- Use worked examples: Worked examples help guide children’s independent practice by demonstrating how they can correctly apply recently learnt material in a step-by-step, easy to follow manner.

- Summarise information clearly: By being clear and concise, children are in a better position to replicate the task, develop their skills and understanding and avoid confusion or learning any misconceptions.

- Model tasks: If you describe which steps you’re taking to complete a task and why you’re taking those steps, children are able to understand the topic easier. Some ways you can be a model is to think out loud, ask probing questions, or use completion tasks.

“The power of teacher modelling lies in finding a good balance with pupil practice. Mode, practice, model practice, review…that’s the cycle that’s needed. My feeling is that we miss opportunities to model and there are still lots of occasions when students go from being told things in abstract to being asked to do things without anyone modelling the process explicitly.”

Tom Sherrington, Teacherhead & Rosenshine’s Principles in Action.

One of the biggest challenges facing teachers is ensuring that our children are learning what we are teaching them. And more to the point, how do we help ensure that any misconceptions that take root early don’t cement into their long-term memory?

By checking children’s understanding in the same sequential process that information should be taught, children are less error-prone in their learning and have a better fundamental understanding of the topic.

Regularly assessing children’s understanding is closely linked to presenting information is small, sequential steps. As our working memory is so small, if children try to summarise too much information at once, their brain can suffer from something known as cognitive overload. Because of it, the learning process can slow down or even completely come to a stop, as the brain can no longer process all the information being presented at that one time.

The likelihood of this overload occurring is especially true if children don’t have a strong fundamental understanding of the topic. Therefore, checking their understanding at regular intervals ensures children aren’t rehearsing misconceptions or misunderstandings into their long-term memory.

Essentially, Rosenshine believes that checking for understanding serves two purposes:

- Checking for understanding typically leads to children explaining their answer, which leads to children making connections to other lesson content and, ultimately, cementing this information into their long-term memory.

- If they haven’t got the answer right, this is key information for teachers to know, as they can identify this as an area that needs to be revisited or retaught.

In the classroom:

- Ask questions – Perhaps the simplest and easiest way to assess how much children know is by asking questions. Probing questions such as “why do you think that is?”, elaborative interrogation questions such as “why is this true?” and pre-questions are some great questioning strategies teachers can use to check for children’s understanding.

- Ask students to summarise – Summarising information is another great way to see if children have fully grasped the points and concepts you’re teaching them, especially if it’s a complex process or topic. Asking children to paraphrase or summarise this information forces them to engage with the material more deeply and establish what the key information is and what information is ignored, resulting in better memory recall.

- Harness the Testing Effect – Having low-stress daily, weekly and even monthly quizzes is a great way to monitor children’s progress — retrieval practice works best when the stakes are low. This is because the word “test” can strike fear into the heartsof children. So, by using informal assessments, children can use these quizzes for what they’re meant for: to check the depth of their understanding. An alternative way to check children’s understanding is to do a short interactive activity for five to ten minutes which forces children to think about an answer to a problem.

- Check students’ responses – The best people to assess whether they’re confident with new material are the children themselves. When teaching new material, teachers can ask children to use hand signals or signs to indicate their level of confidence in their understanding. For example, using their fingers, children can rate their understanding on a scale of one to ten. Alternatively, children can use individual whiteboards and hold their answer up to the problem presented so teachers can assess individual understanding whilst doing whole class activities.

How to check for understanding

- Cold calling

- Whiteboards “show me”

- Say it again, better

- Process questions

- Probe deeper

- Feedforward comments

- Think, pair, share

- Pose, pause, pounce, bounce.

By having high success rates for tasks set during lesson time, children will perform better when practising alone as a result.

Rosenshine suggests that the optimal success rate a teacher should strive for is 80%. This is because an 80% success rate highlights that children are understanding material and effective learning is taking place, but it also shows that children’s understanding is being challenged.

If children were consistently getting 90-100% on their tasks and assessments, it may indicate that the material is too easy. In contrast, the overarching benchmark of 80% highlights that child learning is predominantly error-free and children are more confident in their academic ability.

One of the most common misconceptions about motivation and success is that the former leads to the latter. But the reverse is also true. By obtaining a high success rate, we increase feelings of mastery and confidence, which serve to boost future motivation for the task.

In the classroom:

- Have high expectations – Rosenshine emphasised that having a high success rate relied on all children achieving at least 80%, not just a minority of students carrying the class average. It is important that your expectations apply to all your children.

Research shows that having high teacher expectations can significantly improve academic achievement. This is often referred to as the Pygmalion Effect which is when people raise their achievement in order to live up to someone else’s high standards and expectations. On the other end of the spectrum is the Golem Effect, which shows how having low expectations of your students can hinder their performance.

- It’s about balance – Achieving a success rate of 80% also relies on teachers observing and regularly assessing their children’s knowledge to determine whether lesson plans need to be altered in any way.

If your children aren’t performing well academically, then it may be worth dedicating more time to re-modelling and re-teaching information so they can develop stronger foundational knowledge of the topic.

On the other hand, if the success rate is too high, you may need to challenge children by making assessments harder, asking them to engage in more critical thinking, or provide them with ample opportunities to learn independently.

Have students acknowledge their successes – Part of this principle is based upon the emotional and motivational boost children will get when they achieve success. It is probably also in part based on the importance of learning information on a deep and fundamental level, so that it could be built on later. Therefore, it is important that children are aware of their successes in order to get the most benefit from them.

Rosenshine proposes the temporary use of scaffolds, to provide children with the appropriate amount of support they needed during the learning process. This support should be given until children are confident and successful in their ability to complete a new task.

Scaffolding can be defined as the process of gradually removing your support as the child masters a new skill or concept. Teachers should remove all support when the child is fully confident they can successfully complete a task on their own and have demonstrated as much. However, if children get stuck on a more challenging version of the task, they still need help. This style of support helps children grasp concepts a lot more quickly and guide student practice. Rosenshine calls this process “cognitive apprenticeship”, as children learn effective strategies that enable them to become successful learners.

One important element of scaffolding that teachers should pay attention to is anticipating the common errors and misconceptions their children may fall victim to when completing a new task, and spend time explaining why they are common errors. For example, in maths, not considering the units of a value when subtracting one from the other (i.e 4L of milk is separated into 100ml bottles. How many bottles are there?). By highlighting these errors to students, they’ll be less likely to store them in their long-term memory.

The concept of “scaffolding” was developed by Lev Vygotsky. Vygotsky believed that the cognitive development of a child was enhanced through the use of collaborative learning methods. By communicating with adults and teachers (people that Vygotsky described as a ‘More Knowledgeable Other’ (MKO)), children were able to make sense of the world and engage with their learning.

Vygotsky found that students who received help from a MKO when completing a new or difficult task that was slightly beyond their ability performed significantly better when asked to complete the same task on their own. Because of this, Vygotsky proposed that all learning takes place in something called the zone of proximal development.

This zone can be defined as the difference between the child’s actual developmental level and the potential level they could achieve with the help of adults or more experienced peers. To progress through this zone, children need guidance from their teachers – otherwise, they won’t be able to reach their full potential.

In the classroom:

- Use checklists or structure – Providing checklists or writing frames such as PEEL paragraphs is a great way for children to check that they are completing work correctly. You can give children common error checklists or questions that they can reference to make sure they’ve included everything they’re supposed to.

- Model task completion – Describe and show children the steps they need to take when completing a task. This stops children from making common errors and allows them to obtain a clearer understanding of what they’re expected to do.

- Ask probing questions – Ask questions such as “which part of the equation would you solve first?” or “why do we need to expand quadratic equations to solve the question?” This will encourage children to think critically.

- Use Elaborative Interrogation – Alternatively, children can engage in Elaborative Interrogation such as asking “why is this true?”, which enables them to make connections to prior knowledge.

Teachers should not only make independent practice a mandatory part of their lessons – they should monitor children’s practice as well. This is so the knowledge and skills that children acquire becomes automatic to them and memory recall is easier.

And the more children engage in independent practice, the more likely they are to become mature, independent learners that take responsibility for their learning.

Rosenshine takes the stance that the more a child practises, the better their learning gains will be.

It’s important that guided student practice and independent practice are not confused with one another. Guided practice is when teachers support children’s learning by providing models and using scaffolds until children feel confident and are successful in their attempts to complete a new task. Independent practice typically follows guided practice and is when all support is taken away so “overlearning” can occur.

“Overlearning” is when children practise a task again and again until they can complete it fluently and without errors. As a result, their newly acquired knowledge becomes so automatic that it doesn’t take up space in their working memory anymore, which makes them less likely to experience a cognitive overload. This enables children to focus on further developing a deeper understanding of new lesson content and successfully applying their newly-learned skill.

Rosenshine emphasises that the lesson content children practise independently should be the same as what they’re practising during guided practice. This is so children are fully prepared to engage with the material on their own and are less likely to practise making errors.

In the classroom:

- Prioritise mastering a skill – Research shows that there are two types of motivation that children feel:

- Mastery-orientation motivation

- Ego-orientation motivation

The first describes children who enjoyed improving and developing their skills as they feel most successful when they’ve mastered a task. The second type of motivation is driven by the need to know where they rank against their peers, and those children feel most successful when they’ve done better than others.

However, children who have ego-orientation motivation tend to have lower levels of confidence, motivation and self-regulation, perform worse academically and have increased anxiety as a result of this constant comparison. Therefore, it’s important that children understand why they should set goals for themselves and not just to prove something to others. This way, they’ll be more inclined to work, even when no one is watching.

Avoid things such as class rankings and putting everyone’s grades on the board for the whole class to see. Encourage your children to reflect on how they can get better and what environment they perform best in. Not only will children focus on their own progress more, but it’ll be easier for them to pinpoint areas they may need to do further independent practice on.

- Watch out for the Planning Fallacy – 75% of children consider themselves procrastinators. For 50% of those children, procrastination has become such a norm that it’s problematic. Higher levels of procrastination are associated with low self-efficacy and has a detrimental effect on children’s academic performance. However, research suggests that for some children, procrastinating on a task may be unintentional. The reality is that children fall victim to the Planning Fallacy, which is when a person underestimates how long a task will take to complete.

Research shows that 70% of children reported finishing their work a lot later than what they had originally predicted. By underestimating how long a task will take, children don’t spend enough time engaging with the task on a deeper level, reducing the quality of their independent practice.

One way for teachers to help children overcome this is, when setting work, they should provide a rough estimate of how long the task will take so schildren can set aside an adequate amount of time.

- Focus on the why – children need to realise why independent practice is important – otherwise, they’re not going to have that motivational edge. Getting children to think about the “why” forces them to think deeply about a topic. By self-reflecting and thinking curiously, children learn topics faster and have better memory recall as they understand the topics they’re learning a lot better.

Pushing your children to think critically about their learning also helps develop a sense of purpose. Research shows that children who were taught why completing a task was beneficial to them were more likely to put more effort into completing it, thanks to higher levels of intrinsic motivation. Encouraging self-reflection and goal setting amongst your children and connecting material to the real world are a few ways teachers can help their children develop a sense of purpose.

Regularly applying newly learnt information to complete tasks, be it through answering questions, quizzes or past papers, improves memory recall.

Rosenshine believes that for children to become skilled and successful learners, they need additional practice to ensure this information is well connected and embedded in their long-term memory. When connections between learning are widespread and far-reaching, learning actually becomes easier because children have a strong factual foundation. Regularly reviewing information frees up space in our working memory: trying to remember old information won’t get in the way of trying to learn new information.

Research shows that children who were given weekly quizzes scored significantly better on their final exams compared to children who were only given 1-2 quizzes per term. Another study found that even when the quiz didn’t contribute to their grades and only covered some of the lesson material, children who were regularly quizzed over a year and a half scored a full grade level higher on the material from the quizzes.

Rosenshine’s tenth principle embodies the idea of successive relearning, which is the combination of retrieval practice and the Spacing Effect. Specifically, it is when children space out when they practise retrieval over a certain period of time until mastery and automaticity of the skill have been accomplished. For example, continuously expanding quadratic equations correctly and without errors.

Utilising a successive relearning approach when engaging in independent practice is a great way for children to maintain their ability to successfully apply their knowledge. It also enables children to make connections between previously-learnt information and newly-acquired information, allowing them to get a better understanding of the bigger picture and thus enhancing their memory recall.

In the classroom:

- Do weekly and monthly quizzes – Teachers often use formal assessments as a way to assess child understanding. For example, when you’ve finished going through a topic, you may have an end of topic tests. The marks that children achieve on these tests then go towards their current grades. However, retrieval practice may not work as well in this situation.

This is because when children know they’re getting tested on a topic, they may panic or shut down. The issue with the word ‘test’ is that children don’t focus on what’s important: whether they fully understand a topic or need more time practising. Low-stress weekly and monthly quizzes are a great way to monitor children’s progress – retrieval practice works best when the stakes are low.

- Ask questions – Asking students questions and encouraging them to think critically is a great way for children to think deeply about the material they’re learning. Not only do questions allow teachers to assess children’s understanding and whether more time should be spent on providing scaffolds, but they also allow children to practice retrieval.

Using questions such as pre-questions has been shown to improve academic performance by up to 50% in certain situations. Research also shows that children who use self-questioning techniques performed better on their exams than children who either reviewed lesson content by themselves or discussed it with their peers. It’s important that children ask ‘why’ so they can make stronger connections between their old and new knowledge.

Feedback from adults

The feedback children receive about their learning has a significant impact upon their progress; being too general or giving broad targets is not helpful. Giving incisive feedback helps children to understand how they can improve.

Feedback is:

- any information that is provided to the performer of any action, about that performance.

- more effective if it focuses on the task, is given regularly and while still relevant.

- most effective when it confirms the pupils are on the right tracks, gives details of why answers are correct or wrong and when it stimulates correction of errors or improvement of a piece of work.

- effective when suggestions for improvement act as “scaffolding” i.e., pupils should be given as much help as they need to use their knowledge. They should not be given the complete solutions as soon as they get stuck so that they must think things through for themselves.

- quality dialogue – research indicates that oral feedback is more effective than written feedback- therefore all adults are expected to leave a visual footprint in lessons using marking codes to show the verbal feedback they have given.

Verbal Feedback

Verbal Feedback:

The language used in the classroom reflects the ethos of a learning culture within North Mead. Teachers and other adults focus on the fact that challenge means that new learning is taking place. Mistakes are treated as opportunities for improvement and a focus for support.

Oral feedback is provided during every lesson, individually or collectively.

Together We Make A Positive Difference

Together We Make A Positive Difference